Asylum appeals backlog could reach 100,000 cases by end of 2025

The asylum appeals backlog is a lesser problem than the initial decision backlog. But it is harder to solve.

At the end of September 2024, there were 34,000 asylum appeals waiting to be determined by the immigration tribunal. The initial decision backlog stood at around 100,000 cases. There are around 80,000 asylum claims being made per year. The grant rate for initial decisions was 50% but seemed likely to fall. And the immigration tribunal determined 10,000 asylum appeals that year.

So, on the back of the proverbial envelope and by deploying some massive assumptions, we can have a wild guess at how big the appeals backlog might get and how long it will take to clear it, if nothing changes.

“If nothing changes” is a massive and incorrect assumption to make. There are too many variables for what follows to be an accurate prediction. But it is instructive to think about these variables and what they mean for the asylum system in future.

How big might the asylum appeal backlog get?

The existing backlog combined with a further year of asylum claims means a potential caseload of 180,000 by the end of the year if no new decisions were made. Let’s say that caseworkers at the Home Office manage to make 150,000 asylum decisions over the next year, returning the asylum backlog to a steady state of around 30,000 cases. A backlog of 30,000 cases is “about right”, probably. It takes some time — around six months maybe — to fairly determine applications for asylum which are not straightforward.

It is not at all impossible to make that many decisions. In the most recent quarter, officials made only 18,000 decisions, which extrapolates as 72,000 annually. But in the third quarter of 2024, before the last government blew up the asylum system with the Illegal Migration Act, officials managed to make 65,000 decisions, which extrapolates as 260,000 annually. Many of those 65,000 decisions were rubbish but better processes and training could address those issues and lead to a lower but still very considerable total number.

If the initial decisions grant rate stays at 50%, that would mean a further 75,000 or so appeals being lodged in the immigration tribunal over the next year. Not every refused asylum seeker lodges an appeal but a high percentage are thought to (I’d very much like to know this figure, incidentally!). If the initial decision grant rate falls any further, which seems likely on current trends, the number of appeals would be even higher than that.

So, if zero asylum appeals were determined over the next year, that would give us 109,000 outstanding appeals by the end of the year. But 10,000 asylum appeals were actually determined in the last year, so we are looking at basically 100,000 asylum appeals outstanding in a year’s time.

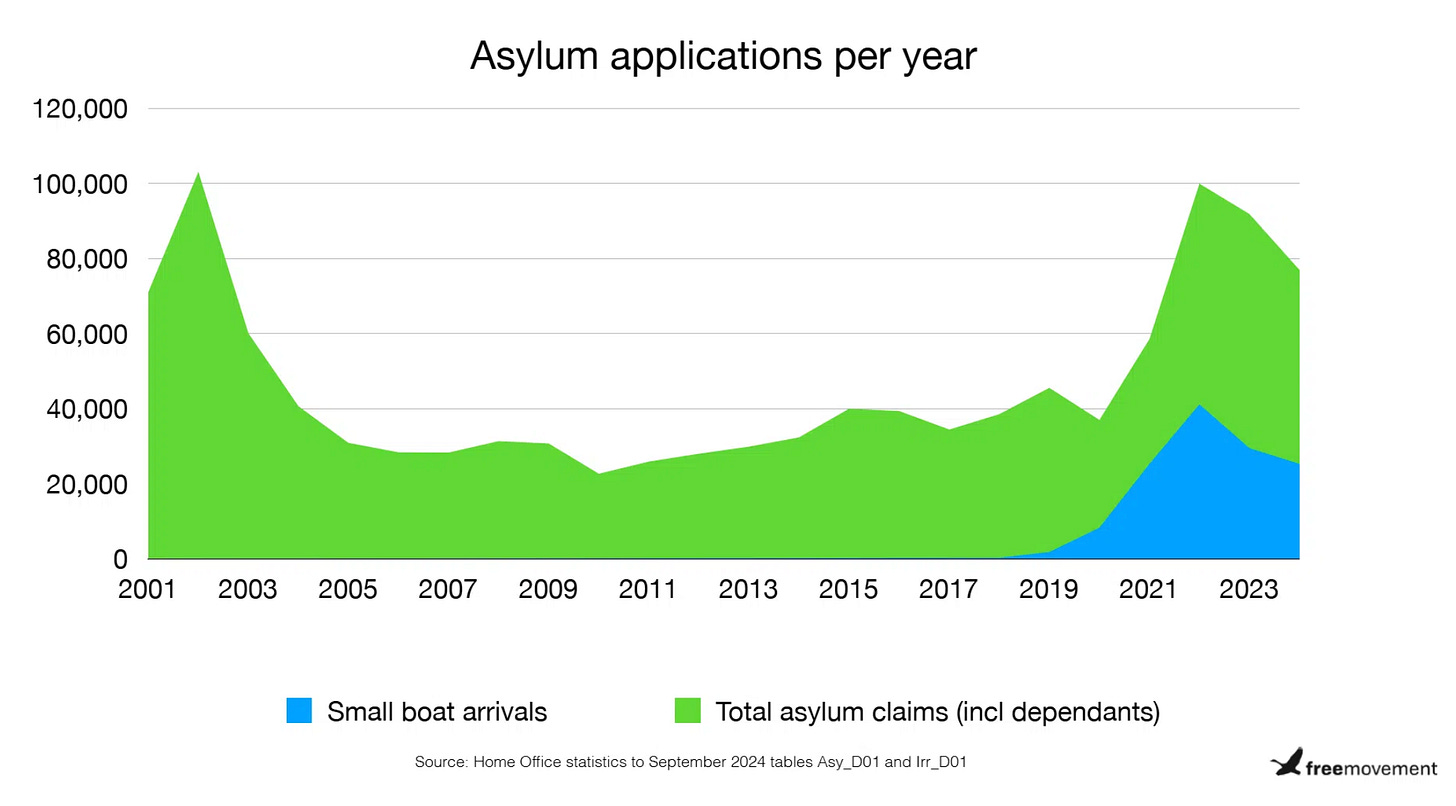

How long would it take to clear that backlog? Well, at least ten years. But there will still be asylum claims being made and determined in subsequent years. There were about 80,000 asylum claims made last year. If around 80,000 asylum claims continue to be made per year and the grant rate continues to be 50%, that means something like 40,000 appeals per year in future.

So, on current trends and if nothing changes (which it will), the asylum appeals backlog would never diminish. It would just grow and grow.

Before I go any further, that number of 40,000 appeals per year is, to me, quite shocking and unexpected. The most asylum appeals the tribunal has determined in a single year since 2007/08 was 21,000 appeals in 2016/17. The number of asylum claims may well diminish further over the next few years. As the chart below shows, volume of claims is on a downward trend at the moment, which would reduce the scale of the task considerably.

What responses are available to the government?

Firstly, things can change in unpredictable ways even without the government really doing anything. But if the government wants to actively manage the number of asylum appeals in the immigration tribunal, it can try to affect inputs or outputs. Or both, probably.

Inputs

If the number of asylum claims made in the United Kingdom were to fall, this would generally lead to fewer appeals being lodged in due course. But, without a returns deal with the EU or France, it is hard for the government to have much of an impact on the overall number of asylum claims.

If the initial decision grant rate changes, this will also affect the number of appeals lodged. An increase in the grant rate (i.e. more asylum seekers are recognised as refugees) will lead to fewer appeals being lodged. A decrease in the grant rate (i.e. more asylum seekers being refused) will lead to more appeals being lodged.

Or the government could start curtailing asylum appeal rights. Or perhaps even other appeals rights, in order to focus more resources on asylum appeals. Neither is a good idea.

Asylum appeals are an essential check on a life or death decision by a very junior government official. They aren’t an annoyance; they are an essential safeguard.

And anyway, any asylum seeker denied a right of appeal can potentially pursue an application for judicial review instead. There is a drop-out rate here (as in, a lot of people do not in fact pursue an application for judicial review because it is hard to do so) but judicial review cases are a lot more cumbersome and expensive than appeals so removing appeal rights is highly unlikely to save time and resources overall. This is precisely why a full right of appeal was introduced by a Conservative government back in 1993, incidentally.

And the system needs some stability. Officials and politicians always like to tinker with the law because it is easy to do. It’s easy to explain to the public and it gives you something to say in the media. But, as the last government definitively showed, passing new laws is not the same as making them work. The whole reason new ministers are in this mess is because previous ministers preferred to pass a bunch of new laws instead of getting on with managing their department properly. The high-level time and resources that law-making absorbs cannot be used, instead, on less glamorous stuff that actually has a real-world impact. And constant change slows real change.

We know what a functioning asylum system looks like. There is no need to reinvent the wheel.

Nevertheless, given the numbers I went through earlier, it seems likely the government is going to be looking at some sort of institutional changes. Perhaps we’ll see the reintroduction of the detained fast track or heavier and reformed use of ‘clearly unfounded’ certificates to deny a right of appeal in some cases.

Outputs

The conventional way to increase outputs is to increase capacity. There are three options here.

First, the government could eliminate some appeals by reviewing previous decisions at an early stage and granting people status. Around half of asylum appeals succeed, so knocking out some of those appeals early in the process would be very sensible.

Second, the government could recruit more judges, hearing rooms, Home Office lawyers and claimant lawyers. This would increase the number of appeals being determined. The problem is that the first three of these resources are fairly easy if perhaps expensive to increase. It is very hard to recruit more claimant lawyers. The sector is tiny compared to previous years and it is hard to build things up from a low base. The Immigration Advisory Service and Refugee Legal Centre, when they were funded by a grant from the Home Office, could previously have helped here. But not today as they both went bust over a decade ago.

But “very hard” is not impossible. Private firms could recruit and train more staff if given enough money. More money is being put into legal aid but it remains to be seen whether this is merely sufficient to stem the outward tide of lawyers leaving the sector by paying them better and not sufficient to attract new lawyers, which is what is needed. Spending more money but not enough to make the required difference would be the worst of all possible worlds for the government. Or the government could recreate IAS and RLC. Although that would require legislation at this point.

Third, the government could increase capacity to hear asylum appeals within the tribunal system’s existing resources.

Asylum appeals are only around half of the tribunal’s existing workload. The other half is mainly human rights and EU rights appeals. Increasing the grant rate and reviewing existing decisions in those categories would free up resources to focus on asylum cases. And being more generous on EU rights is something EU diplomats are very keen on.

There is probably also more the government could do, working with the judiciary, to improve efficiency in the tribunal generally. Last year the tribunal determined a total of about 60,000 appeals. In 2008/09 it was more than 200,000 appeals. Admittedly, many of those were relatively straightforward, which an asylum appeal most definitely is not. But we don’t have to go back many years to see the tribunal determining twice as many asylum appeals as today.

And finally…

The government really, really needs to not make things worse.

If the initial decision grant rate falls any further, that is potentially going to create tens of thousands of additional appeals. Ministers and civil servants need to climb out of their bunkers and see the asylum system as a whole. It’s no use focussing on quality of decisions, or whatever, and thinking “appeals and removals are someone else’s problem”. Appeals and removals are a direct function of initial decisions.

If the Home Office does something to generate a lot more work for itself, that is bound to divert resources away from the appeals backlog. For example, reviewing all Syrian asylum cases, withdrawing asylum or refusing settlement after a safe return review would not help the situation. It would generate thousands of new, unnecessary appeals.

The Home Office needs to find ways to do less and do it better, not more and, inevitably, do everything worse.