High and low resistance deportations

Deportations are inherently challenging. Some are more challenging than others.

I was talking to an academic from the United States recently and he mentioned in passing that the US government funds 400,000 deportations per year. That many do not always take place in a given year but that is the target. And the target has sometimes been met.

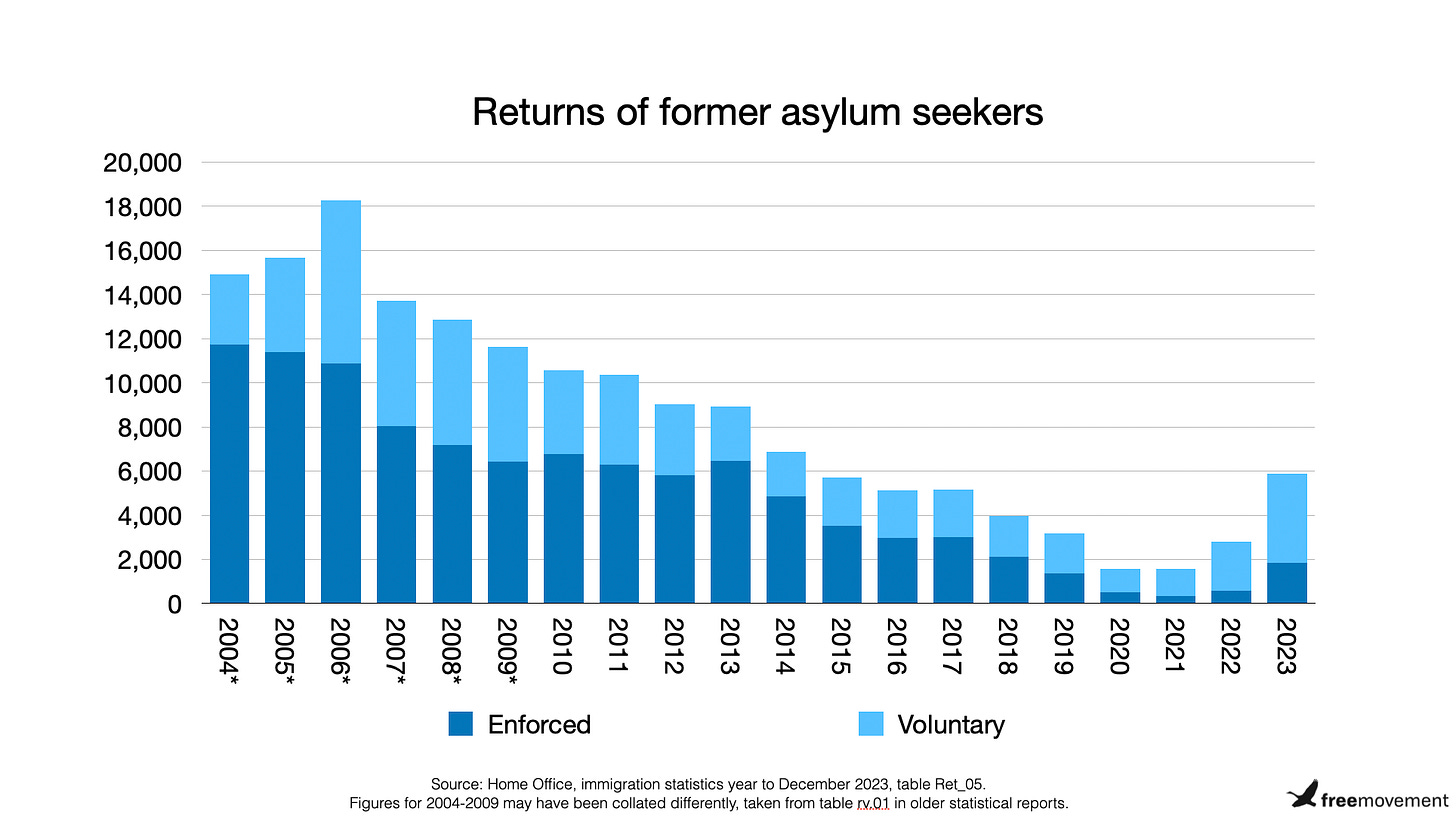

Here in the United Kingdom the highest number of enforced removals of failed asylum seekers was 11,743 in 2004. In the year ended March 2024, a total of 6,956 such removals took place. This was double the previous annual period. The sharp rise was due to a massive increase in removal of Albanian nationals. Over half of the recent removals were of Albanians: 3,898 in total. As we’ve explored on Free Movement previously, the sudden increase in Albanian removals is linked to the sudden increase in Albanian arrivals. The arrivals stopped soon after they began. We can therefore expect the removal of Albanians, and therefore overall removals, to fall back again shortly.

The chart below is for a slightly different period: year ended December 2023, to enable easy comparison with previous years. The total for 2024, on current trends, will be higher than for 2023.

You can take a look at the Home Office narrative and the old and new data tables for yourself.

Even with the recent increase (which is very likely to fall back again), it still looks like the number of removals from the United Kingdom is still half the level of the early 2000s. And why are these numbers so much dramatically lower in the UK compared to the USA? I thought it might be useful to think about the different types of removal. It struck me that some removals might be more consensual than others. I’ve identified three different types of removal to discuss here: voluntary, low resistance and high resistance.

Before I go any further, no decent human says — as Suella Braverman once did — that a deportation flight is their “dream”. Enforced and even voluntary removals are grim, as we will see. This is not a fun subject to be writing on. But departure after a failed asylum claim is part of a functioning asylum system. And the Labour Party has pledged to recruit 1,000 officials to work in a new removals team. What are these officials going to do and can they really increase the number of departures?

Voluntary “removals”

The best way for failed asylum seekers to depart from the country is voluntarily. There are grades of “voluntary” in this context. Some have correctly said that a “voluntary” departure isn’t really very voluntary when the alternative is exposure to the hostile environment and a threat of a forced removal. Here I’m going to define voluntary removal is one where direct physical coercion is not used. Detention and escorts are not used but threats, implicit or explicit, might be.

At the moment, voluntary departures are encouraged by means of both carrot and stick.

The carrot is eligibility for a payment of £3,000. These payments are made in some so-called “assisted removals”, which are removals to a “developing country”. You can read the Home Office policy on all this for yourself.

There are many who will object to a failed asylum seeker being given £3,000. There will be administrative costs on top of that, such as the salaries of the staff managing the scheme and the cost of plane tickets. It costs an awful lot more than that to conduct an enforced removal, though. The cost was estimated at £15,000 back in 2013 but the cost has probably soared since then, and not just because of inflation. We’ll come back to that.

There are several sticks. Denial of immigration status, exposure to the hostile environment, on-and-off immigration detention, the possibility of an enforced removal and a stronger bar on re-entry to the UK that kicks in where a non-voluntary departure takes place are all, in theory, incentives to go quietly of your own accord.

But you can see from the chart above that voluntary departures have also declined, albeit they have recently increased again. Like the increase in enforced departures, the increase in voluntary departures consists mainly of Albanians. The numbers are likely to fall back again in the near future absent further action.

For those interested in the history of voluntary departures, the likely causes of their decline (basically, being taken in house by the Home Office, away from originally IOM and then Refugee Action) and some thoughts on how they might be revamped, I recommend the 2019 report by Jonathan Thomas at the Social Market Foundation.

High resistance removals

At the opposite end of the spectrum to voluntary departures we have enforced removals in which the person facing removal is highly resistant to that removal. These are very hard to carry out. Not impossible, but hard.

They are obviously hardest on the person facing removal. By definition, the person being removed really, really does not want to go. They will be desperate. Such desperation manifests differently for different people. There is a serious risk of the person being harmed, either by themselves or by their escorts. Prominent examples of high resistance removals include the death under escort of Jimmy Mubenga in 2010 and the abortive Rwanda flight in 2022.

You can get a favour of how grim the Rwanda flight was from the introduction to Lizzie Dearden’s harrowing article about it:

Documents released by the Home Office showed that detainees self-harmed, threatened suicide, and were put into “pain-inducing” restraint after begging not to be deported from the UK. One man was found cutting his wrists with shards of a drinks can, while another smashed his head against a plane seat while screaming “No, no” in desperate scenes on 14 June.

To prepare for further Rwanda flights, the Home Office even hired an aircraft hanger and fuselage so that staff could practice the various methods of coercion they considered likely to be necessary.

The Rwanda flights are not unique. If you are up to it, you can read a similar account of what sounds like enforced “Dublin” removals in 2020 of asylum seekers back to EU countries in which they had been fingerprinted.

Those who advocate removals which are likely to end up high resistance ones should really, really think about the human consequences of what they propose. I suspect some don’t think about the consequences at all, or much care. But they should. High resistance enforced removals are grim.

Maybe I am being naive here but I imagine it is pretty traumatising for those conducting the removal; it’s easy for politicians to fantasize about such deportations but someone has to actually make it happen in real life. There might be a few people who get off on forcing a person to do something they really don’t want to do but not many, I hope. It puts me in mind of Mary Bosworth’s study of immigration detention and the staff who carry it out. Those staff who had transferred from prisons found immigration detention far more depressing and upsetting because there was no veneer or pretense of attempting to rehabilitate. It all seemed so totally pointless.

Removal on a scheduled flight without escorts or with a small number would be the cheapest option for an enforced removal. High resistance removals on ordinary, scheduled passenger planes seem to have been diminished over recent years, though, presumably because of Jimmy Mubenga’s death. Perhaps tellingly, the reason they seem to have become less frequent is not that the Home Office decided they were wrong or dangerous but because other airline passengers did. Several accounts have circulated on social media and were reported in the mainstream press of fellow passengers objecting to an enforced removal on their flight, refusing to take their seats or similar. This seemingly led to the captain of the plane then refusing to take off. Several attempted removals were abandoned in this way. A quick Google search shows examples from 2018, 2023, and 2024.

Use of charter flights seems to have become more common, presumably at least in part in response. These involve a private flight being booked to a given country, perhaps stopping at a different country en route. Officials are instructed to start detaining nationals of the relevant countries during their monthly reporting-in to the Home Office or are encountered. Sometimes nationals of the relevant country who have committed an offence will already be held in prison or have been transferred from prison to an immigration detention centre at the end of their sentence. These individuals are then held in detention until the flight takes place. Many end up being released, though, because being detained prompts them to lodge a legal claim to remain. The Home Office routinely regards these claims are vexatious. They certainly are last ditch attempts to avoid being removed. That doesn’t mean they are unfounded, though. Lots of people put off expensive, complex and unpleasant tasks until they have to. With no legal aid for immigration cases, lots of people who have an arguable claim to remain don’t get around to putting it forward until they absolutely have to.

I am not aware of official statistics on the use of charter flights but the Home Office sometimes releases information in press releases and so on. There were “over 130” charter flights in the two year period between April 2020 and May 2022, for example. We do know that they require considerable resources and are therefore very expensive. An account of a charter flight removal in 2020 suggests there were 86 escorts on a flight with 11 deportees, a ratio of more or less 9:1. Even that did not prevent serious incidents of self harm and violent, pain-causing restraint methods were deployed. Those being removed also have to be detained beforehand, which adds to the cost. Given the limited number of detention spaces, it also limits the capacity of the state to conduct such removals.

So, high resistance enforced removals are traumatic for all involved, use very considerable resources and are extremely expensive. There are fewer of them for all these reasons. How expensive? We don’t know. As we saw earlier, the cost was estimated at £15,000 back in 2013. We don’t know how that figure was calculated but the apparent rise in the use of charter flights compared to scheduled flights suggests the total might be a lot higher than that today.

Low resistance removals

Self evidently, enforced removals will be easier to carry out where there is low resistance from the person facing removal. They might even be persuadable to go voluntarily or might be removable on a scheduled passenger flight.

What might make a person less likely to resist their removal? This is hard to say and I’m not aware of any research on the subject. I’d guess a combination of factors such as:

Do they have strong ties like a partner and children in the UK who will not relocate with them? If so, we might expect them to be highly resistant to being removed. Having your personal and family life permanently destroyed is a big deal.

Is there a significant disparity in life chances or outcomes between the UK and the country to which they face removal? Is there an ongoing conflict there or natural disaster? If so, they might well be very unhappy about going.

How final does the removal seem or feel to the person concerned? Where there seems some possibility of return, even if it is in reality somewhat illusory, resistance to departure might be lower.

What is the geographical distance between the UK and the country to which the person is being removed? If it is a long way and the person invested a lot of resources in reaching the UK, they might well be resistant to being removed again.

How familiar is the person with the country to which they face removal? This is one issue with Rwanda removals: it is removal to a totally unknown country where the person cannot imagine how they will survive or make a future for themselves or their family. Even with removals to the country of the person’s nationality, the fact they have a nationality does not mean they are familiar with it. They might have left as a child or even been born in the UK, not acquired British nationality but have inherited the nationality of a parent. Removal to a completely strange country, particularly combined with other factors, is likely to be very distressing.

Does the person feel they’ve been unfairly treated? Sheer human stubbornness is quite a thing. Where someone feels like they have not had a hearing, that their situation has not been considered, then they might well be more resistant to removal. It’s not that knowing their case has been heard would make them happy to go, but they might be less unhappy about it.

This might explain how the United States has been able to conduct so many forced removals. I’ve no doubt that there has been a high degree of violence involved and an awful lot of resources, but even then it seems like an awful lot of removals. I would guess a lot of those removals were to Mexico or to central or South American countries. The stakes will at least in some cases be a bit lower for removal back to a country you have already passed through or are actually from.

I’ve been meaning for ages to look up where the 12,000 or so removals back in 2004 were to. I suspected most of them would have been to European destinations. I thought that removals to European destinations would have been easier for the reasons I outline above. It seems possible that resistance to removal would probably have been lower to those destinations. I’m not saying anyone would have been happy about being removed, just that they would have been less resistant than to some other destinations.

I was part right. This is the breakdown by the major regional groupings used by the Home Office:

European destinations: 4,820

Sub-saharan Africa: 1,982

North Africa: 505

Asia South: 1,691

Central and South America: 952

Middle East: 813

Asia Central: 618

Asia East: 272

Asia South East: 65

The bulk of those removals to European destinations were to Serbia and Montenegro, including Kosovo (1,518), Romania (877), Albania (635), Poland (286), Czech Republic (234), Lithuania (110) and Moldova (104).

I’m not going to go over the current removals statistics in detail — this is not a cheerful subject and I’m keen to write on something else, frankly — but a very high proportion of current removals are also to European destinations. These are removals of foreign national offenders rather than asylum seekers. Again, it seems unlikely that many of those facing removal are pleased about the situation (I don’t know how many lodge appeals against their deportation, for example), but being removed to a European country with which you are already very familiar and indeed come from is a lot more palatable than being removed to a strange country or one that is far, far away.

Conclusions

The Labour Party is apparently interested in increasing the number of immigration removals and have committed to recruiting an additional 1,000 officials to work on this. Removals are not easy, as we’ve seen, but they are something the government can control. Unlike small boat arrivals. What might these newly recruited officials work on?

Increasing voluntary departures is the least violent, least coercive, most obvious and cheapest option.

Increasing the available payments might help a little, which are currently set at £3,000.

Voluntary departures were more popular when handled at arms length from the Home Office, by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and by Refugee Action.

People might be more willing — or, at least, less unwilling — to make voluntary departures if they have fewer links to the UK and have lived here for less time than at present; the asylum backlog means people have been waiting years for even an initial decision, and that is before appeals are taken into account. Faster decisions might on average make voluntary departures more likely.

The asylum grant rate has fallen very rapidly and there will be a considerable temptation to curtail appeal rights and/or accelerate appeals. Both of these factors may cause some people to feel they have been treated unfairly and make them more resistant to departure.

Similarly, detaining people first and asking questions like “do you have a case to stay here” afterwards is a massive waste of everyone’s time. When someone has a case to put forward to stay, of course they put it forward if they get detained. This is probably one of the reasons why the proportion of people being released from immigration detention into the community has risen. If detention is to be used, it should be a last resort. Detention should be one of the last stages in a managed, multi-step departure process, contingent on all else failing.

At the moment there are two legal barriers to a deported person returning to the UK. One is a set of immigration rules that prohibit a person from returning lawfully within a certain time in certain circumstances. The other is the practice of visa officials to refuse the re-entry of family members if they have previously breached immigration rules. The test is supposedly very high (“contrived to frustrate in a significant way”) but experience suggests that spurious reasons for refusal are given instead. As a lawyer, it’s impossible to advise a person that if they do the “right” thing and leave, they will be able to re-enter if they meet the rules. The reality is that they will be refused, making the departure prolonged or even permanent. Both these barriers to return should be reconsidered because they are a contributing factor to reluctance to leave in the first place.

It might be possible to target voluntary departure packages at nationals of some countries over others. It seems inherently unlikely that a refused Afghan or Iranian might want to make a voluntary departure, for example.

Some of these ideas could also be adapted or applied to enforced removals. The less resistant people are to being removed, the better - for all concerned.

There’s one thing that is beyond the control of the government, though: where a person is from and therefore to where they can be removed. It is all very well saying that it might be easier to remove people to European and certain other countries but that may not be from where asylum seekers come. If the next government is set on increasing removals, it may well find it tempting to prioritise some nationalities over others.

Another word for this is discrimination. Why should one person face enforced removal because of their nationality when another does not? Omitting to pursue enforced removals of some individuals because of their nationality would feel unfair to those targeted instead and it would be a bad look in the media. There’s plenty of official and unofficial discrimination in immigration law and practice — think of the visa nationality list as a starting point — and so it would not be entirely unprecedented. And wasting everyone’s time, money and energy detaining people who are unlikely ever to be removed, even if that is partly due to their own conduct, is also bad. Personally, I suspect this might be a contributing factor to the fall in enforced removals: bad decisions to detain reducing the effective detention and caseworking capacity of the Home Office.

I haven’t looked here at the competence and caseworking ability of Home Office officials; this article was about a more specific subject. But anyone who, like me, has undertaken work for Bail for Immigration Detainees will know just how arbitrary and pointless many decisions to detain a person are and how arbitrary decisions are about ongoing detention as well. Detention decisions are often highly opportunistic rather than strategic. Reviews of detention are often highly defensive of the original decision. As a result, the people who are detained are often not the people who might potentially be removable. There are only a limited number of detention spaces. Building more would be incredibly expensive at a time when there isn’t much money available. If the government is serious about increasing removals, it would need to use those detention spaces more wisely.