Immigration as contract: care visas and international students

What the Migration Advisory Committee annual report tells us about recent migration trends

The government’s Migration Advisory Committee has published its annual report for 2023. It’s long but worth at least a skim if you are interested in immigration policy. There’s a pretty detailed look at how net migration works, for example, and then the report goes on to consider some specific policy areas. The two on which I’ll focus here are social care visas and students.

I’ve been meaning to write up some examples of what it might mean to think of immigration as a contractual arrangement and this is a good opportunity for that exercise.

Health and social care visas

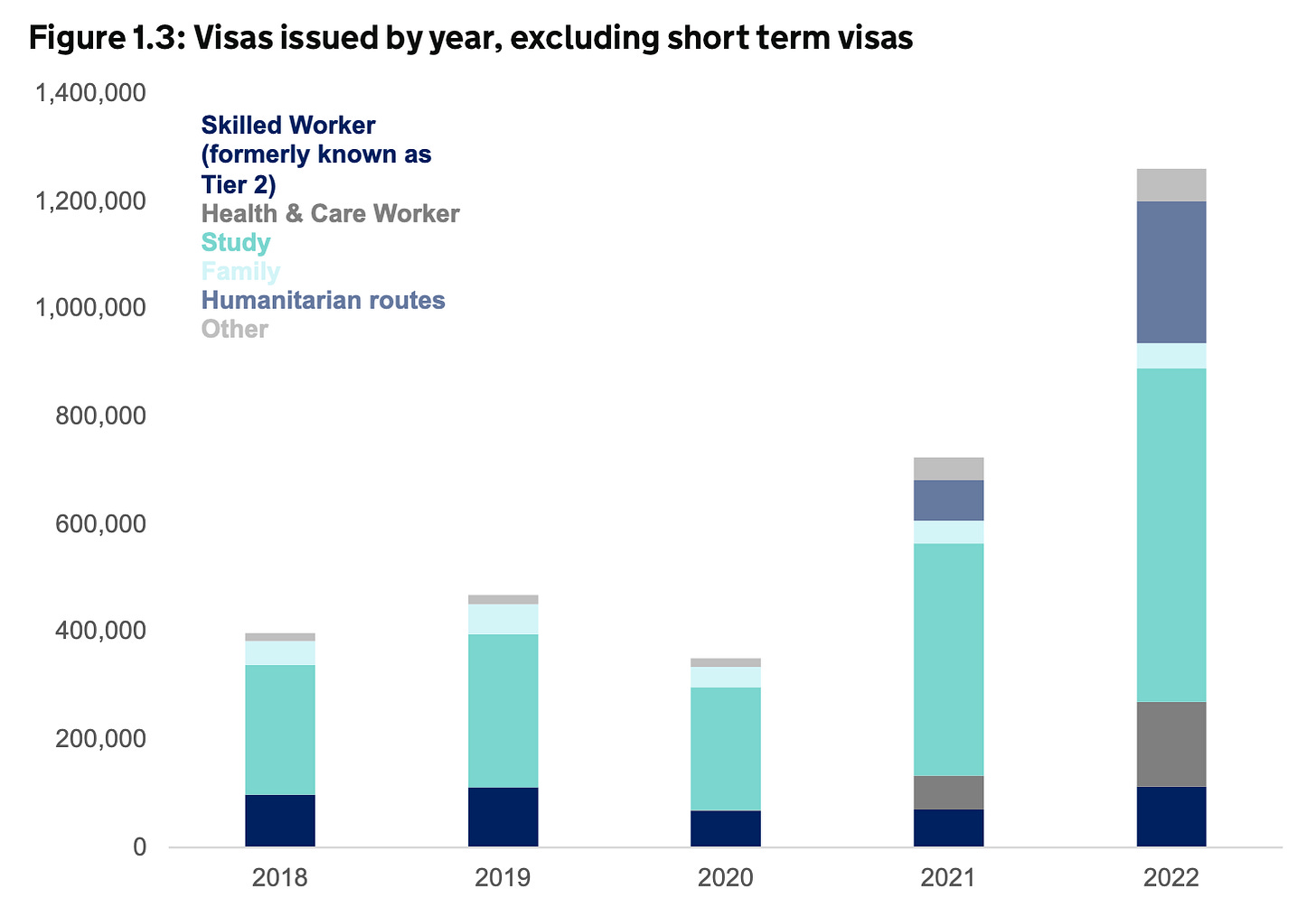

There has been a rapid rise in the number of health and social care worker visas issued, from a very low base to 142,800 in the year ended September 2023. That’s nearly 70% of all skilled worker visas issued. This alone has made a very significant contribution to net migration, not least because those workers have only just arrived and none will have left so far.

The MAC report records that the number of vacant posts in the adult social care sector fell by 7% over the last year. MAC concludes that

The extension of the visa route to care workers has therefore eased the workforce pressures in the sector and surely improved the availability of care received by clients.

The government has not implemented the MAC recommendation to mandate a minimum rate of pay in the social care sector of £1 per hour more than the National Living Wage. With higher pay, more workers in the UK might be willing to do those jobs.

Instead, the government has maintained the lower qualifying salary level for health and social care visas but banned workers from bringing dependents with them. The MAC report notes that the potential impact on the migrants themselves:

it is likely to disproportionately affect women, lead to migrants being more isolated and therefore potentially susceptible to exploitation, and lead to long separation of families.

My own view is that if we’re going to recruit overseas workers at artificially low rate of pay to do difficult jobs in the UK on the basis that they are so low paid and difficult that those already in the UK will not do them, we should treat those workers with respect. Banning them from bringing their families, particularly when around two-thirds are women, is not respectful and will lead to family separation, which means children growing up without a parent.

Some will say that the worker concerned need not come; they can stay in their own country if they don’t want to be separated from their families. I’ve got some sympathy for this approach and have said so on social media. Ultimately, it is true that most migrants do not need to come to the UK.

The exception, to my mind, is family members of citizens and long-term residents. Which is why I am so strongly opposed to the massive increase to the Minimum Income Rule for sponsoring spouses and partners and to the punishing fees these family members also have to pay.

This thinking is based on what has been characterised by Hiroshi Motomura as the “contractual” model of immigration. If you sign up to the terms of a visa route and knew what you were getting yourself into then that’s on you. If you are a competent adult, you have agency and can make your own decisions.

This breaks down if unexpected things happen. If you are exploited, that isn’t something you signed up to. There is evidence of exploitation occurring, as the MAC report explains.

If the terms on which you originally entered are changed after your entry, that isn’t something you signed up to either. This also happens. The government regularly hikes application fees even for those who have already entered, for example. This could totally change your cost-benefit analysis and it could force you out of existing accommodation and to reduce remittances you planned to send, for example.

There are some other serious issues with this contractual approach.

One is that the potentially vast disparity in earnings and life outcomes for migrants and their children may well drive a migrant to accept appalling terms as a condition for migration. It is not a case of two equals negotiating a fair contract.

To illustrate this, think about the new ban on dependents for health and social care workers. It might lead to a change in who comes; it might be childless men and women who take up the visas in future. It seems far more likely that it will actually be the same demographic who continue coming — women from certain countries — but they will have to leave their families behind in future. That is very hard on them and on their families. But they’ll probably do it anyway on the basis that after five years they can apply for settlement and at that point they can apply for their families to join them, at least as long as the children are still below the age of 18 then and they can earn enough to sponsor them. Or that they can earn sufficient money in the meantime to make it worthwhile anyway, no matter the short term social and emotional costs.

Or a migrant might willingly commit to even massive recruitment fees and a claw back clause — effectively turning them into a modern indentured labourer — if they take a long view.

A contractual thinker will say that’s fine, the migrants can decide for themselves. But it looks pretty exploitative to me. And it’s not likely to lead to happy, well-integrated workers either.

International students

The MAC report looks at the two big development in student immigration: an overall increase in international student visas and an unexpected increase in family members of students.

On the students themselves, the government announced that it wanted to increase international student numbers. It did increase international student numbers. Universities have an incentive to recruit more international students because this helps to compensate for frozen funding levels. The increase is therefore a success story.

The more interesting change was family members of students because this increase was not expected.

The MAC report rather wryly observes that MAC recommended against the creation of the graduate work route in 2018 on the basis that it might “incentivise demand for short Master’s degrees based on the temporary right to work in the UK, rather than primarily on the value of qualification”. Which appears to be what has happened.

In contrast, the government’s impact assessment on opening the graduate route failed to anticipate what would happen: a sharp increase in the arrival of family members of students.

The impact assessment did not anticipate the change in countries of origin of students from Chinese (low number of dependents) to Indian and Nigerian (comparatively higher number of dependents).

Nor did the impact assessment anticipate the changed incentive for bringing dependents, with student visas extended for an additional two years by the graduate route. Student visas would now typically last for five years for undergraduates and three years for postgraduate Master’s students.

The blanket ban on bringing family members imposed on postgraduate Master’s students may have unanticipated effects, the report notes. It will likely discourage older students, female students and disabled students and is likely to have more of an impact at some institutions than others.

Thinking about students through the lens of a contractual view of immigration, perhaps this tells us something about the need for careful contract design. James Cleverly, the Home Secretary, described migrants bringing their dependents as “abuse”. That is obviously very wrong; all those migrants were doing was making a cost-benefit analysis and applying under existing rules. They read the small print and they liked the look of the contract on offer.

What Cleverly should have said but could not for political reasons was that the change in demographics was unexpected and unintended as far as the government was concerned.

The contract was badly drafted. But there was no bad faith or breach of contract on the part of the migrants concerned.