We have lots of refugees but no refugee integration strategy. Which is bad.

We do everything we can to alienate and break refugees. And then eventually make them part of our society anyway.

The recent, belated and much-needed acceleration in Home Office asylum decision making means that a lot of asylum seekers are now, at last, becoming recognised refugees. The old backlog will hopefully diminish rapidly now. What happens to the new and growing backlog of asylum claims made after 28 June 2022 remains to be seen.

But what will happen to the thousands of asylum seekers who suddenly find themselves with legal status? The Home Office operates in a state of constant perma-crisis; the question is always where the crisis will manifest next. It is like squeezing a balloon. Grasping one problem causes others to bulge up elsewhere.

Lots of asylum decisions = lots of new refugees

The Times reported on 3 September 2023 that just over 2,000 asylum decisions were made in the previous week. Some of these may have been so-called “withdrawals” — essentially, the Home Office taking an asylum seeker off the books for some minor perceived or actual administrative failure by the asylum seeker — but it looks like a lot of proper decisions must be being made as well. This is reported to be in large part because full asylum interviews have been dropped for asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Libya, Syria and Yemen and certain claims from Sudan.

Basically, it sounds like nationals of those countries are simply going to be granted asylum, subject to security checks. This is what many of us have been suggesting for a long time now. You can see from this slightly ugly Home Office chart that some of the major countries of origin of asylum seekers coming to the UK have very high success rates (marked with an ‘x’ on the chart).

Ultimately, it just isn’t that hard to grant asylum to someone from, say, Syria, when its nationals have a 98% success rate. What on earth officials at the Home Office have been doing with their time before now is a mystery.

The overall asylum grant rate for the year ended June 2023 was 71%. Of those who appeal against a refusal, a further 53% win their appeal. So, lots of asylum decisions means lots of newly recognised refugees plus a relatively small number of failed asylum seekers.

What happens when asylum is granted?

As Sonia Lenegan, the new Editor at Free Movement, explains here, when an asylum seeker is granted asylum, they will have to leave their Home Office-funded asylum accommodation and they will lose their Home Office-funded asylum support. That’s good; asylum accommodation is terrible and asylum support is miserly. It’s part of transitioning properly into British society.

They will be granted leave to remain for five years. In theory this can be taken away if their country becomes safe; in practice this is very unlikely. At the end of the five years, they are eligible to apply for settlement, formally called indefinite leave to remain or sometimes permanent residence.

Once they have that grant of legal status and proof of their legal status the idea is that they can either find a job and a place to rent or they can access mainstream welfare benefits if they need to.

They absolutely need proof of their legal status because employers will not usually give anyone a job without such proof, nor will landlords rent property to anyone without such proof. At the moment the fines for doing so are £15,000 per worker and £1,000 per occupier respectively. These are due to rise to £45,000 and £5,000 per person at some point in the near future (a VERY bad idea, as discussed here previously).

And you cannot claim normal welfare benefits without proof of your legal status either, so the Department of Work and Pensions will simply send you away.

The problem Sonia explores is that the Home Office is failing to issue proof of legal status (called a biometric residence permit) promptly but evicting recognised refugees from their asylum accommodation and cutting off asylum support anyway. Newly recognised refugees have no prior notice of what was coming — after waiting for years for a decision, remember — and will have just a few days to find a job or contact their local authority for support.

The result is that a newly recognised refugee will often find themselves with no asylum support but also unable to work or rent accommodation and unable to to access the welfare benefits to which they should theory be entitled. They will almost inevitably therefore be homeless. They will become the responsibility of the local authority where they were then resident.

Local authorities have had as little notice as the refugees themselves.

Recap: our refugee integration strategy is what?

So, as I said recently on Twitter/X, our refugee integration strategy is:

Keep asylum seekers waiting for years for a decision on their asylum claim. I’m not sure what the average waiting time is now but it must be at least two or three years. Some have been waiting longer.

During that time, prevent them from working. Remember, there is lots of evidence to show that the longer you are out of the labour market, the harder it is to get back in and there will be long term adverse consequences for your earning capacity as well.

Accommodate them in remote former military barracks in rural areas, cheap hotels in poorer areas and, briefly, in disease-ridden floating hulks.

Allow them just £8.24 per week in support money, meaning they have almost no capacity to do anything.

Subject them to constant hostile rhetorical abuse, singling them out as a pariah group. Enable far-right demonstrators and upset local residents to target them and protest against them. The asylum seekers as well as the population will bear witness to all this; everyone understands that asylum seekers are officially unwelcome.

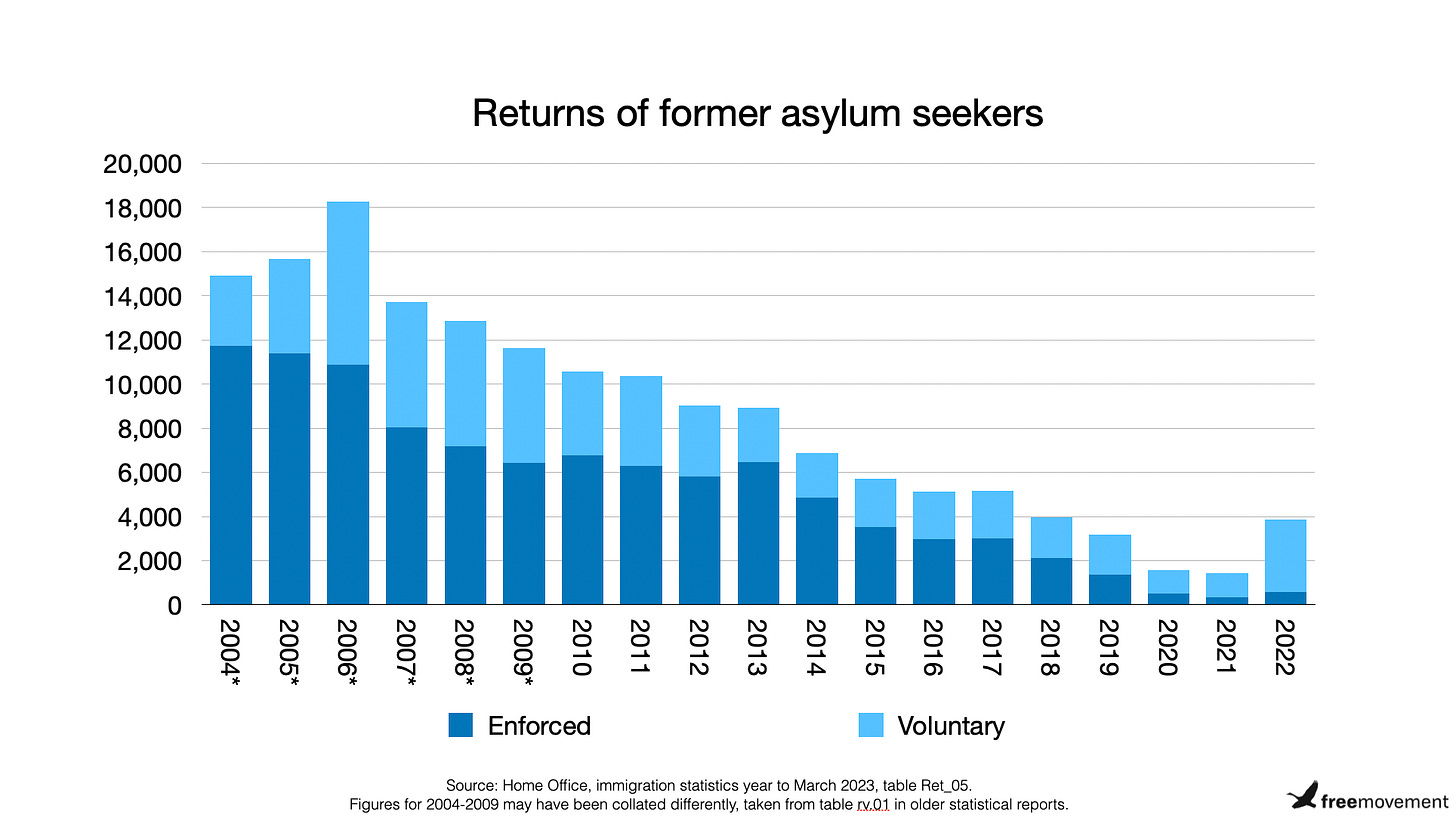

Grant some 80-90% of them asylum, which is effectively permanent residence because of the right of renewal after five years. They become a permanent part of British society. Even where asylum claims are rejected, failed asylum seekers are also effectively a permanent part of British society as well because enforced removals and voluntary departures are very low.

Delay giving these newly recognised refugees the biometric residence permits they need to work and to rent accommodation.

This effectively forces them into homelessness and makes them the responsibility of the local authority where they happened to be accommodated. It is probably more expensive to the overall public purse than a planned, longer and supported transition to lawful status, but the Home Office doesn't care about that because it’s no longer their budget.

Complain that refugees do not integrate properly and have worse socio-economic outcomes than others.

That is, by any rational standard, absolutely crazy.

The harsh treatment of asylum seekers is a long-standing policy dating back to the 1990s, when asylum success rates were as low as 4%. It kind of makes some rational sense from a policy perspective if:

It deters other asylum seekers from coming (it doesn’t)

It is only for a short time (it isn’t)

The people you do this to aren’t refugees and aren’t allowed to stay (they are).

The approach belongs to a time when asylum decisions were fairly rapid, the vast majority of asylum claims would be rejected and thousands of those failed asylum seekers were removed or made voluntary departures. None of that is true any more. Asylum claims have been taking years to decide and then the vast majority of people are allowed to stay, either lawfully or tacitly unlawfully.

How about the Illegal Migration Act?

I don’t know what to say about this. I increasingly feel like campaigners should ignore it because it is so obviously unworkable it will have to be abandoned very rapidly if it is ever implemented. Time and energy spent on it is time and energy wasted. It is different for lawyers because the government seems hell-bent on removing at least a handful of people to Rwanda and they desperately need representation.

If the Illegal Migration Act is ever activated, the government’s plan is that every asylum seeker arriving after an as-yet unannounced date will either be removed to Rwanda or kept in the UK in a new perma-backlog. None of them will ever receive an asylum decision here in the UK. There will be no recognised refugees in future.

There are two ways it might play out in practice. I wrote a full Substack article about it here if you want to go into detail.

If it goes according to plan, the removal of a relatively small number of asylum seekers to Rwanda will suddenly stop the boats or severely diminish the number of arrivals. Ongoing removals to Rwanda will be necessary to maintain the deterrent effect but not in significant numbers.

No-one actually thinks that is going to happen.

It is possible the government will strain every sinew to try and make it happen anyway, building huge detention camps and forcing ever-increasing number of refugees onto flights to Rwanda. Some may be deterred but undetected arrivals would probably go up and anyone not detained will simply disappear into the community rather than risk removal to Rwanda. There will be a large official backlog of people who are either in detention or who have disappeared who will in theory one day be removed to Rwanda. And there will also be a large but unknown number of people who arrived undetected and never claimed asylum because there was no longer any point in doing so.

Needless to say, creating a large permanent-backlog of people you one day might remove to Rwanda as well as an unknown number of unauthorised entrants who try to stay below the radar is not a good integration strategy. The vast majority will in reality stay in the UK permanently, so this approach will cause huge social damage.

What would a more rational approach look like?

A planned and supported transition to lawful status would surely have better long term outcomes for refugees themselves and for the public purse than the abrupt eviction approach currently being pursued.

Even just a longer transition period could have major beneficial impact. Back in 2018, the Red Cross criticised the existing policy of allowing 28 days as being too short a time. They recommended it be increased to 56 days. Instead, the Home Office have quietly and unofficial reduced the transition time by changing their administrative practices.

The cheapest, easiest and most effective single thing the government could do, though, is make asylum decisions more quickly. I think it is hard to appreciate how damaging it is to refugees for them to be subjected to enforced idleness for such a long time.

It’s a form of prison-like sentence, essentially. Their liberty and agency is effectively removed by forcing them to live in an allocated place that is not of their choosing. Sometimes these are literally prison-like places, such as former barracks surrounded by barbed wire with a lockable gate or a floating hulk. Or they are forced to share rooms with other inmates. And we allow them so little money they can do nothing. They cannot work or study or even volunteer. And they are kept like this for years on end.

Personally, I’d like to see asylum support increased and asylum accommodation improved. But if asylum seekers are only exposed to those appalling conditions for a short time then it is at least less disastrous than at present.

So the first thing I’d suggest is: stop treating them like that for such long periods. Make quicker decisions. It would free up a huge amount of money within the Home Office budget, be far better for refugees and it would also be far better for British society.

If decisions cannot be made quickly — within about 6 months — then another alternative would be to allow asylum seekers to work. This is not just cheap in the sense that it costs nothing. It also saves asylum support costs and generates tax revenues. There’s a big campaign to allow asylum seekers to work but to my mind very quick decisions is a better solution.

As an aside, allowing asylum seekers to work isn’t the same as them actually finding work. Employers might well be reluctant to offer work to people who might be refused asylum and banned from further work at any time. Jonathan Thomas at the Social Market Foundation recently published an interesting report looking at the issue: The sound of silence: Rethinking asylum seekers’ right to work in the UK. It’s an interesting report but to my mind Jonathan overthinks this one. Rapid decisions cuts through a lot of the issues and is a better, much more politically palatable solution. His discussion of whether failed asylum seekers who have found jobs might be allowed to continue working as a means of encouraging employers to take them on in the first place is interesting. It’s probably not very realistic given that it would even further undermine voluntary departures, though. Enforced removals and voluntary departures of failed asylum seekers — there are comparatively few of them these days because of the high grant and appeal success rates — are likely to be a major focus for a new government, I’d have thought.

A lot of people just don’t care about refugees. In fact, many think that they should be treated badly. They welcome headlines about barges and homeless refugees. Perhaps this is because they think it will deter others. Perhaps they think it will persuade some to leave. Perhaps they think probationary members of our society should be subject to a sort of socio-economic hazing process to test their mettle. Perhaps it is because they just don’t like refugees or the colour of their skin or their religion.

But causing refugees such harm with such deleterious long-term consequences for their integration and then allowing them to stay long-term seems like the worst of all possible worlds.

After a bit of time off over the summer, I put this article together quickly because it is timely. There has been a sudden and rapid increase in positive decisions and, because of Home Office poor practice, concomitant increase in refugee homelessness. I promise I’ll get back to the series on family immigration policy shortly, though!