Labour's inbox: asylum issues

What asylum and immigration issues are Labour going to have to deal with? And how?

From the Rwanda policy, small boat arrivals and the asylum backlog(s) to workplace raids, foreign criminal deportations, detention spaces, the Windrush aftermath, skilled worker shortages and family immigration rules, a lot of asylum and immigration issues landed on Yvette Cooper’s plate on Friday afternoon when she was appointed Home Secretary.

And as important as all these issues are to some of us working in the immigration sector, they will be towards the bottom of her immediate list of priorities. She also has to contend with security threats — probably one of her first briefings by civil servants — the prisons crisis, policing and the criminal courts backlog.

But it is asylum and immigration issues which have a habit of dethroning Labour Home Secretaries, which seem to preoccupy so many journalists and which will no doubt be used as a weapon by what remains of the Conservative Party.

So, some thoughts follow, building on some of the earlier Substack and Free Movement posts I’ve been working on. I’m working on a series of three “inbox” articles. This first one is about the key asylum issues. The next will look at immigration issues. The final part in the series will look at arguably the most important subject: the approach and culture of the Home Office.

Small boat arrivals

The reality is that the British government cannot directly control the arrival of small boats across the channel. This is the key difference with Australia, which saw a small number of large boats in a massive ocean being detected and then towed to the departure countries, with the consent of those countries. None of that is possible in the narrow English Channel with large numbers of very small boats. And this is why the Rwanda plan was born: the idea was to remove after arrival, not intercept at sea as had been done in Australia.

Co-operation with the French and the EU is therefore required. There are two broad options here. I cannot really comment on how likely, if at all, either might be.

Some sort of bespoke beach-return deal. This would presumably be the ideal outcome for the British government. Basically, anyone detected on arrival would be immediately returned to France or the departure country. Detention would be for a very short time and anyone returned would be placed back in the position they were in literally hours earlier. It’s not like being removed to Rwanda. Resistance to removal would therefore probably be lower and removals probably easier. It seems possible, perhaps even likely, that this would reduce crossings over time, perhaps very dramatically. But why would the French agree to this? The French already received twice as many asylum claims as we do. It would leave them having to process all the asylum seekers who reach France, although those numbers might fall over time. The UK could agree to admit some of those asylum seekers to have their claims decided here, but not if they have crossed the channel without permission. Those numbers could perhaps be very substantial.

A return to the Dublin system. I still cannot believe the UK government barely tried to remain part of this system given the system was so weighted to UK interests. I put together a long read in 2021 on this topic. Since Brexit, the EU has reformed the Dublin system again to make it even more weighted to the interests of countries like the UK. Except we’re no longer part of it. Somehow opting back into this system is unlikely to have an immediate and dramatic impact on small boat crossings, but it might have some impact over time and it would boost asylum removals. Some non-EU countries participate, including Norway and Switzerland.

How likely is it that either of these could be negotiated? I don’t know. But it was a Labour government that negotiated the Le Touquet treaty and UK immigration officials operating on French soil, both of which seemed pretty surprising at the time.

Initial decision backlog

A lot of attention has rightly been paid to the backlog of initial asylum decisions. While there are still a LOT of decisions that need to be made, I think this is largely a problem easily solved. The last government recruited a huge number of caseworkers and trained them up and, until fairly recently, they were making huge numbers of decisions.

The only thing that has stopped them continuing to work their way through what is left of the backlog is the Illegal Migrant Act 2023. A section of this was brought into force which prevents status being granted to successful asylum seekers. It was absolutely insane to bring this into force, but there we go. It is not hard to either find a technical work-around or, more likely, simply scrap that section.

Once that legal change is made, the caseworkers — who I believe are still in post but mainly twiddling their thumbs right now — can resume the work for which they were recruited.

There are some long term issues about efficiency of decision-making and the asylum process but these are not as pressing right now. More immediately relevant is the type of decision that is reached by officials. If a decision is a refusal, the person concerned will usually appeal. The combination of the sheer number of decisions and a falling grant rate has generated a LOT of appeals. A significant appeals backlog is therefore building, albeit much smaller than the initial decision backlog was.

Asylum appeals backlog

While an asylum seeker pursues an appeal, they entitled to be accommodated and supported by the Home Office. A large appeals backlog is therefore, as things stand, expensive. And there is a large and growing backlog of asylum appeals.

The First-tier tribunal disposed of 9,943 asylum appeals in the whole of 2023/24 and just under 40,000 appeals in total of all varieties. But the tribunal received 29,172 asylum appeals and 58,000 appeals in total in that same period. The open caseload increased very rapidly from 30,000 appeals in the second quarter to 50,000 by the fourth quarter.

This is a much less straightforward problem to fix. It is not as much of a problem as the initial decision backlog because it is numerically smaller. But unless action is taken it will take years for these appeals to be processed and this will also gum up other immigration appeals.

Possible options for remedial action include:

Reallocate huge resources to appeals. The initial decision backlog was relatively easy to address: recruit lots of fairly junior civil servants and train them up. This was not without challenges but was easily within the control of the Home Office. It is much harder to deal with appeals in a conventional way. Each appeal needs a judge, a hearing room, a Home Office lawyer and, ideally, a claimant lawyer. Without a claimant lawyer, appeals take longer to process and are less likely to lead to fair outcomes. Less fair outcomes means more refused appeals, which means more people in theory to be removed by the Home Office. Removing people is really hard and really expensive: see below.

Reform the appeals process. This is hard to do at all. The basic structure of an asylum appeal has been pretty stable for a long time now. There are powerful reasons for this, some good and some bad, but all hard to shift. It is even harder to do sufficiently quickly to make a difference in the near future. We can expect the Home Office to look at reintroducing fast-track appeals, work on which has been going on for some time now I think. If too fast, though, these risk being unfair, leading to new problems. There are perhaps other reforms that could be explored but that’s beyond this article right now.

Mitigate the cost. Granting a right to work would reduce the cost to the taxpayer because some asylum seekers with pending appeals would be able to support themselves. The success rate of asylum appeals has been 50% for several years now and seems stable. Nevertheless, this might be politically unappetising. In my view there’s a much stronger case for allowing asylum seekers to work at the initial decision stage after, say, six months because a higher proportion of them will ultimately succeed in their claims.

Reduce incoming appeals. There are two ways this can be done. One is to stabilise or even increase the grant rate for initial decisions. Having stood at around 75% for the last few years, it fell to 43% in the first quarter of 2024. That means a LOT of extra appeals coming through. If around half of these appeals succeed, that’s a colossal waste of time and resources; better to just grant them at the initial stage instead. The other possibility is to continue refusing cases but limit appeals anyway. This can be done by using clearly unfounded certificates, which remove the right of appeal, or by more underhand means such as treating claims as withdrawn. Both of these “solutions” arguably create more problems than they solve. Clearly unfounded certificates can still be challenged by way of judicial review, which is expensive and takes ages. When an asylum claim is treated as withdrawn, the person does not disappear from the country. They are still here and their situation will need to be addressed somehow at some point. The initial asylum process, as expensive as it is, is actually a pretty quick and cost-effective way of doing that compared to fresh claims and human rights claims years down the line.

Reduce number of outstanding appeals. Again, there are two ways this can be done. One is to review outstanding appeals with a view to granting status to those with strong cases that are likely to succeed on appeal. Historically, the Home Office as an institution assumes that asylum judges are simply wrong and misguided. Maybe so, but they are the ones who decide appeals. Continuing to fight a case that is likely to be granted by one of these judges is bloody-minded idiocy and a waste of taxpayer’s money. The other is to find sneakier ways to have appeals treated as abandoned. Again, this creates more problems than it solves because the people concerned are still here.

The easiest and cheapest of these options are (3), (4) and (5), with (4) and (5) being the least politically unpalatable. Relatively speaking.

Removals

Increasing removals of failed asylum seekers is a high priority for the incoming government. I’ve written recently on how difficult it can be to effect removals. Some people really, really do not want to leave and it takes considerable resources as well as outright violence to make them.

I don’t think many people really understand that there is a degree of consensus to quite a lot of state coercion. Prison, policing of demonstrations, immigration detention, passport queues at the airport and so on rely on a sort of threat of violence that both sides usually understand won’t actually be required. There’s a sort of code, though. If the implicit threat is perceived as too token then control is lost. And control will be lost anyway on some occasions.

There’s no code and no consensus to some enforced removals. Death sometimes ensues and there’s always a high risk of injury to both the person being removed and those attempting to remove them.

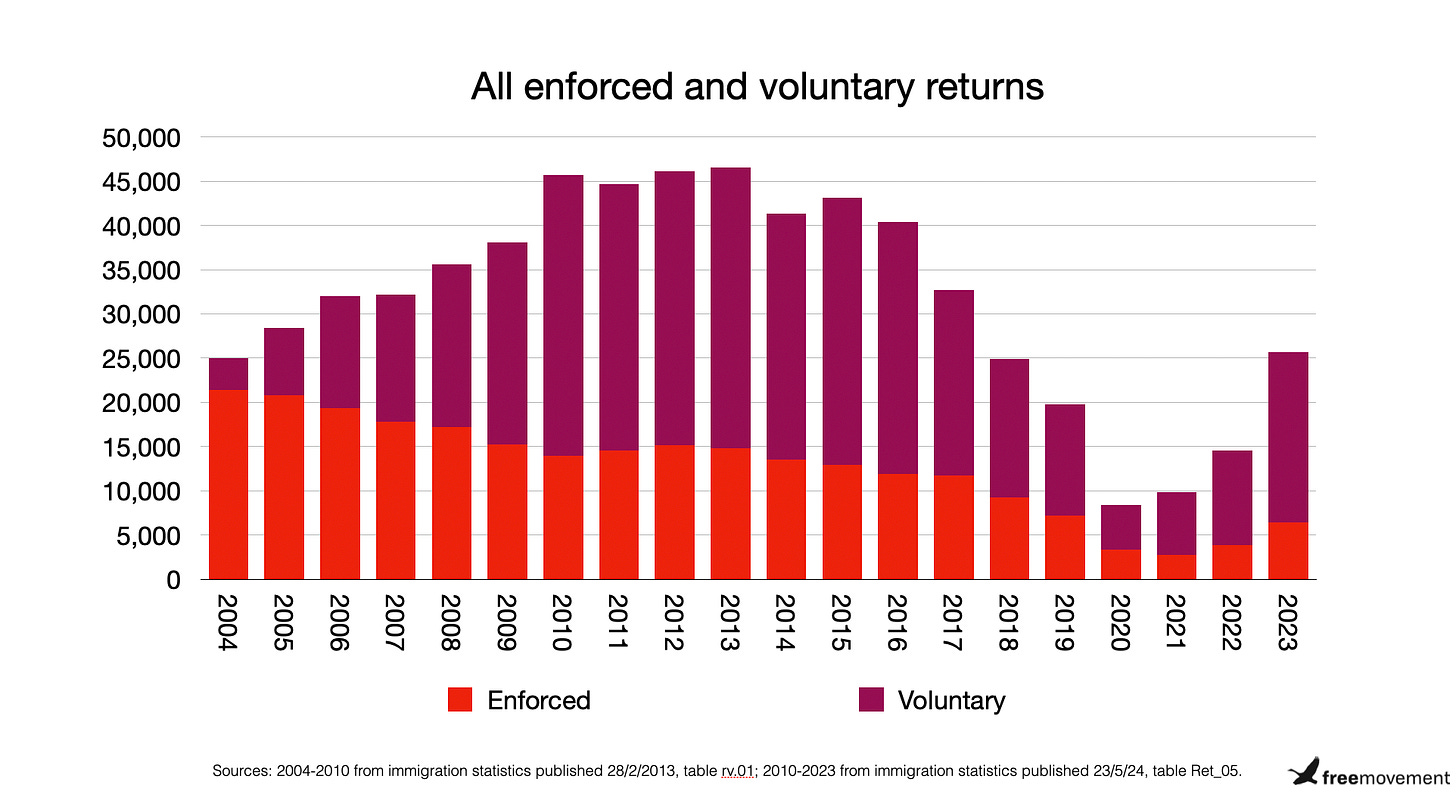

The following chart shows asylum and non-asylum departures. There has been a recent increase in both enforced and voluntary departures. This is mainly due to the departure of a significant number of the Albanians who arrived in 2023.

Options to increase removals include:

Allocating huge resources to indiscriminate removals, no matter how difficult to enforce. This means more detention spaces, more charter flights, more backroom officials to process the paperwork and more officials trained in the use of violence.

Prioritising easier removals. This might mean people who have been in the UK for shorter periods or are facing removal to relatively stable and wealthy countries, for example. But issues arise around fairness — this is discrimination based on nationality, when it comes down to it — and also potentially incentivising people to be difficult.

Smarter use of resources. There’s a limited number of detention spaces. Many of these are filled by people who are never likely to be removed who are detained for primarily political reasons. They have committed serious offences and/or come from countries it is very hard to remove to. It is politically difficult to release such individuals, of course. Detention decisions often seem unplanned and opportunistic, meaning that work to remove a person seems to begin after the person is detained, not before.

Boost voluntary departures. There are several things that can be done on this front, including returning management to an external organisation, increasing payments and reviewing legal (dis)incentives.

None of that is easy. But removals are broadly within the control of the government, unlike, say, small boat arrivals.

Next up: immigration

Tomorrow I’m planning to turn to a series of immigration issues. These include boosting growth, integration, inwards immigration, skilled migration, family immigration rules, the hostile environment, ID cards, deportation, detention and Windrush.

After that, I’ll draw some of those issues together to take a look at Home Office culture and approach and how this might be reformed and why. If you’re interested, please do subscribe!