What might a radical centrist asylum policy look like?

Labour’s recent asylum announcements are starting to piece together a plausible programme for government

It is impossible for the UK government to unilaterally “stop the boats”. As Rishi Sunak is finding, it is very unwise to make promises you cannot keep. Labour should learn from Sunak’s mistakes and stop doing the same.

Here’s three major policy planks they could offer instead.

Firstly, they ought to work to shift the narrative away from irregular arrivals. That is not easy but focussing in on removals might offer a way forward. The focus on irregular arrivals is incredibly damaging for any government and causes public anxiety that in turn makes it more politically challenging to advocate for humane asylum policies. If we can move on from irregular arrivals, hopefully we can move on from the failed but pernicious idea of deterrence.

Second, a deal with the EU would offer possibilities for genuine control of the border. International co-operation and solidarity are classic centre-left pursuits. Labour are clearly on to this already, as the news today shows.

Finally, a party of the centre left really ought to be thinking about social impact, equality, productivity and growth. There are some very easy and cheap wins available on refugee integration, which would also have the beneficial side effect of reducing unnecessary work at the Home Office.

Change the focus from arrivals to removals

Labour could make a specific, ambitious but achievable pledge on removal of failed asylum seekers and announce a new voluntary departure scheme. This provides a plausible narrative on control of asylum. It is also a point of comparison with past and present Conservative governments that Labour could surely bang on about in future for evermore should they choose. And it is similar to what Tony Blair did in 2004, and successfully followed through on, since one of the big questions in centre-left politics at the moment seems to be ‘what would Tony Blair do?’

Recent Conservative governments have removed very few failed asylum seekers. Around 580 were removed last year and a further 3,280 made voluntary departures. This compares to around 90,000 arrivals, 5,700 negative decisions and a further 5,400 asylum claim withdrawals.

The reasons for the fall in removals are not clear. It is likely to be a mix of a decline in asylum claims from European countries (relatively easy to remove people to), simple deprioritisation within the Home Office and bureaucratic change such as cessation of the fast-track detained system.

Also, very importantly, there are fewer failed asylum seekers right now than in previous decades because of the high asylum grant rate.

However, the government is currently processing the strong asylum cases first, so we can expect the grant rate to fall sharply for a while once decision-makers get to low grant rate nationalities. Once appeals are (eventually) determined, this will rapidly increase the number of failed asylum seekers.

There are three different areas of focus to consider here. One is the use of immigration detention. Another is the prioritisation and processing of enforced removals within the Home Office. The last is voluntary departures.

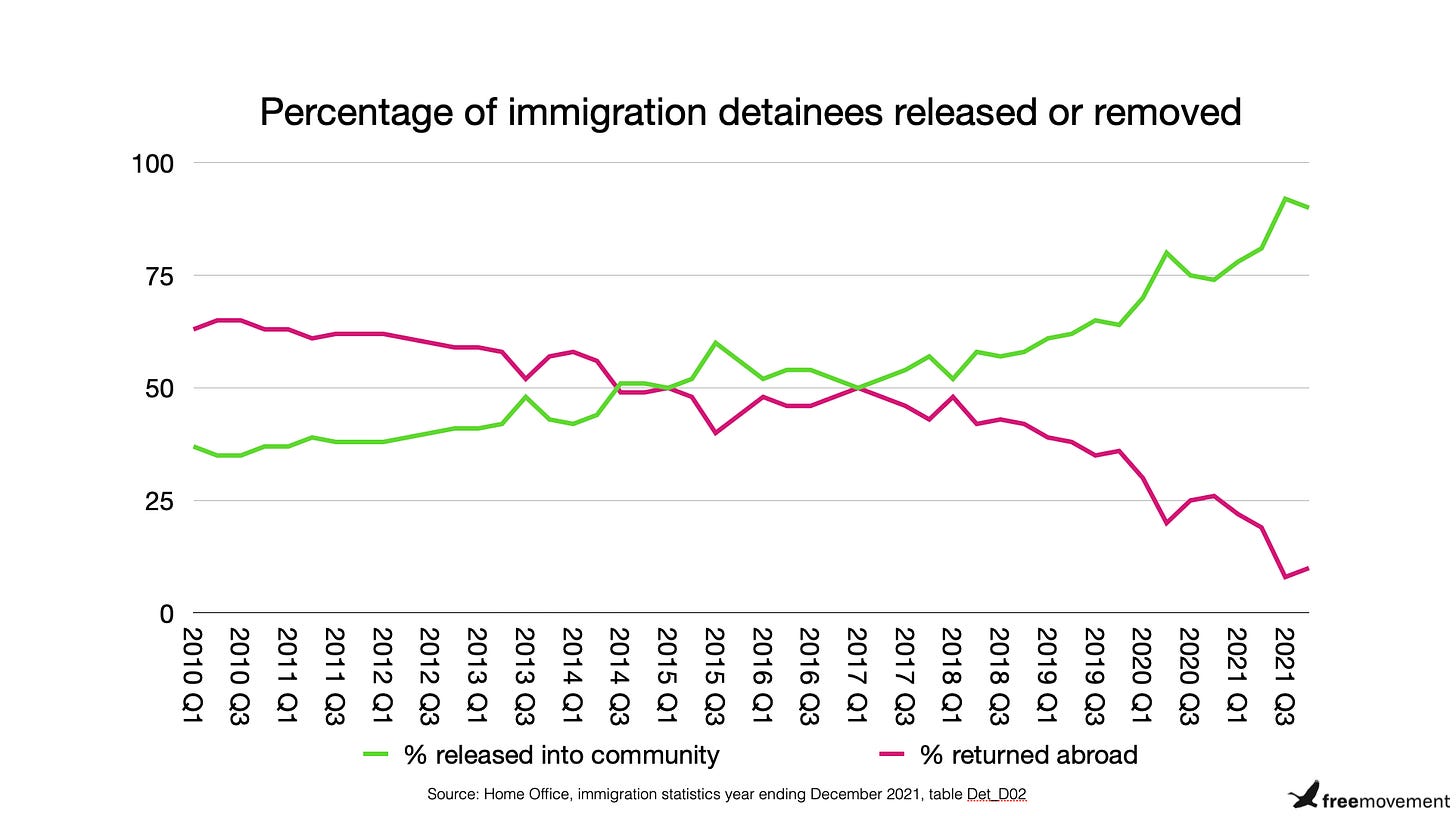

Immigration detention centres are full of migrants who will probably never be removed from the UK but who, for political reasons, civil servants are unwilling to release. Basically, any foreign national who has committed a criminal offence ends up in immigration detention for a protracted period until a judge orders their release. Civil servants, acting on the implicit or explicit instructions of government ministers, are unwilling to release foreign criminals. The headlines in the right wing press are all too easy to foresee.

But another way to see this politically-inspired internment system is as a form of bed blocking. Decisions to detain are often made randomly and opportunistically rather than strategically. Detention spaces are limited. They are being wasted on migrants who can never be removed. The government should focus on detaining people who can be removed, and detaining them as close to the point at which they can be removed as possible, so as to minimise the period they are detained and maximise effective use of the detention spaces available.

It is not easy nor is it pleasant to force people onto planes to countries they do not want to return to. It is also incredibly expensive. The cost was estimated at £15,000 per removal back in 2013 and has soared since then. Few other than Suella Braverman dream of accomplishing such things, although I imagine some of those actually responsible for carrying out the removals might have nightmares about it. But it is something the Home Office used to be able to do better than it does now.

Reports by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration are littered with examples of terrible case management, awful information management and even worse people management. Every report features serious and dedicated civil servants who basically don’t really know what they are really supposed to be trying to achieve or how. It’s not unrealistic to think the key parts of the department could be better managed than they are now. And a big part of that would be de-politicising detention and removals so that civil servants can focus on high risk and/or removable migrants instead of worrying about the Daily Mail headlines that follow release of an unremovable foreign criminal.

On assisted voluntary returns, the Social Market Foundation think tank produced an interesting report back in 2019 (press release / report). They sketched out means by which voluntary departures could be revived, having fallen massively in recent years. Voluntary departures are clearly preferable in every way to forced removals, even if there are questions about how truly ‘voluntary’ such departures are.

Securing the departure of failed asylum seekers is, unlike arrivals, something that is potentially within the government’s control.

Negotiate a returns deal with the EU

Sending an asylum seeker back to France or an EU country through which they travelled puts them back in the position they were in previously. Sending an asylum seeker to Rwanda puts them in an entirely new and dramatically worse position; it is a punishment.

What might a returns deal with the EU look like? Self evidently, it would need to have benefits to the EU as well as the UK. Preventing the build-up of refugees in northern France might be one benefit. UK money might be another. UK humanitarian assistance in providing sanctuary to a fair share of the refugees reaching the EU might be another.

Instant returns deal

The only kind of returns of agreement that might genuinely “stop the boats” would be one involving almost-instant return to France or the relevant country of departure. This would make the journey to the UK functionally pointless and news would rapidly spread by word of mouth in France (unlike with removals to Rwanda, where those removed are in Rwanda, not northern France).

It seems unlikely that such an arrangement can be negotiated, irrespective of whether it would be desirable or compatible with international law. And even a deal like this would present practical as well as humanitarian and legal issues. At the moment the Channel operation is a humanitarian one, and a largely successful one. It would become a security operation, with the relatively few trying to cross using riskier routes and cross undetected. We’d presumably see refugees returning to the use of lorries instead. The numbers entering would, I would guess, be quite dramatically lower though.

Return to Dublin

In the absence of an instant-returns deal, some capacity to remove asylum seekers to EU countries within the framework of EU law and the ECHR would still be extremely valuable to the UK government, particularly given the very, very low numbers of asylum removals at present.

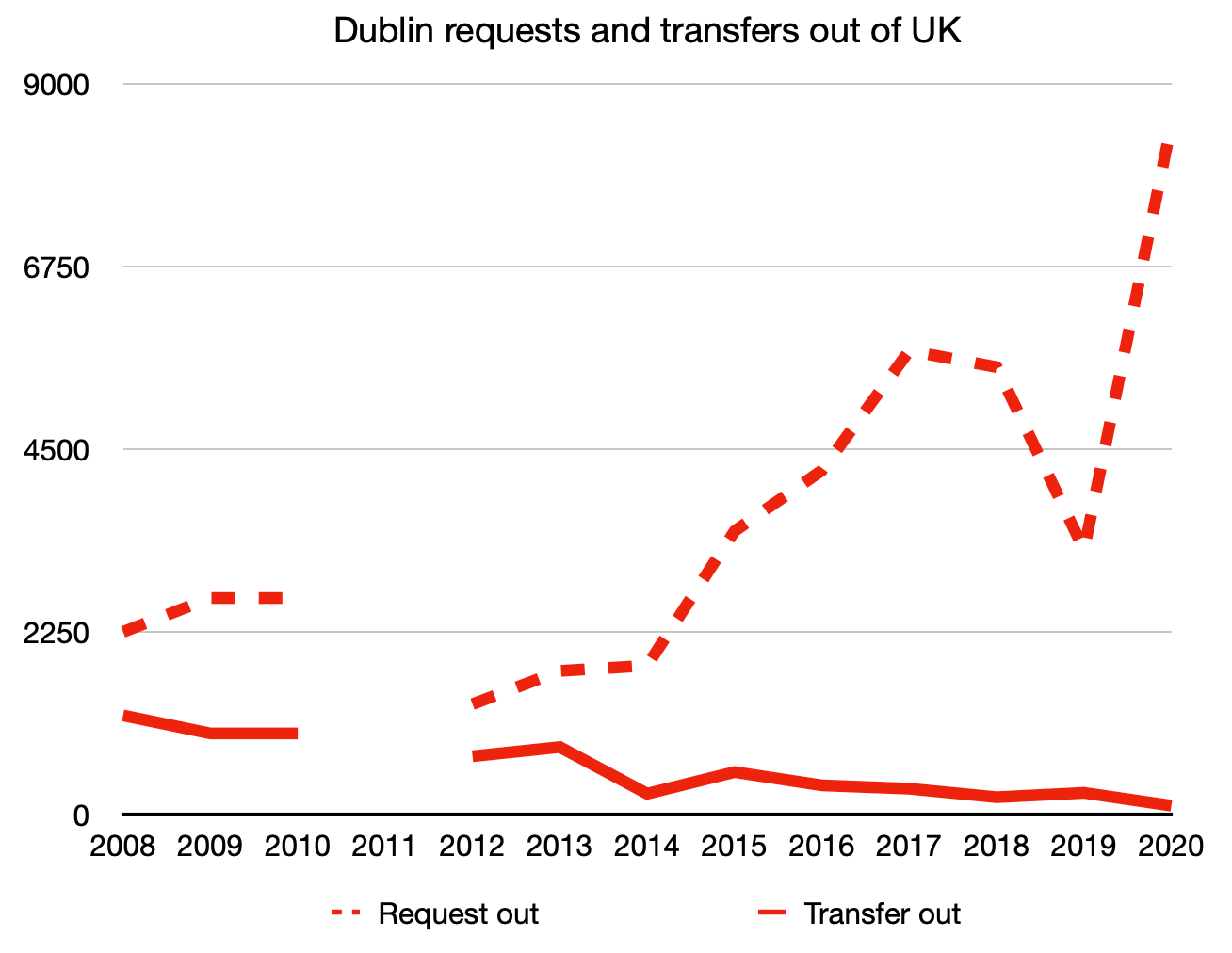

The old Dublin system that the UK left behind with Brexit has been cast by pro-Brexit commentators as ineffective. It is true that it never worked as smoothly for the UK government as they UK government would have liked. In fact, by the time of Brexit more people were entering the UK under Dublin than were being expelled.

But other comparable countries were able to remove far, far more asylum seekers to other EU countries than the UK.

Why was that? Until immediately prior to Brexit, the Home Office had simply given up attempting Dublin removals. There was a renewed focus on Dublin in 2019, leading to a tripling in the number of take-back requests.

Typically of the Home Office, these were all completely pointless because they were automatically abandoned when Brexit occurred and master-negotiator David Frost failed to negotiate continued participation.

Rejoining Dublin would not be a panacea. But it would enable some removals to EU countries. A renewed focus and competent management within the Home Office could dramatically increase the number of such removals. There seems no obvious reason the UK could not rejoin.

Participation in new quota scheme

The EU may not move quickly but it does move. Negotiations have been going on for years to replace the Dublin system with something new. If or when that replacement is adopted is unknowable, but the UK could try to secure participation in it.

At the moment, the deal seems to involve interior EU countries away from entry points for refugees either accepting a certain number of asylum seekers every year or paying into a joint EU fund. It sounds like a notional number of refugees each country ought to accept based on population would be calculated. This would be coupled with a quicker and tougher asylum procedure in border states for those deemed unlikely to be accepted as refugees.

This has been incredibly controversial within the EU. The final version to emerge from the EU Parliament may look different. But if there is some sort of quota scheme or countries can offer to resettle a certain number of refugees from border states or pay into a fund if they wish to accept less than the recommended number, the UK could offer to participate through resettlement and payments in exchange for an instant-return deal or something of that nature.

In principle, UK participation in a European resettlement system, thereby accepting a fair share of the refugees who reach Europe, seems entirely proper. The numbers of refugees being resettled to the UK might well end up being lower than the current numbers who arrive by irregular means under the Conservative government. It would

Boost growth and help refugees integrate

It is disappointing not to have heard anything on this issue from Labour so far. But they have pledged to accelerate the asylum process and, indeed, to actually process asylum claims. That, as I discuss here, is a major component of an effective refugee integration strategy.

Before going any further, bear in mind that around three out of four asylum seekers will eventually be recognised as a refugee. A lot of current asylum policies were introduced at a time when very few asylum seekers would ever be recognised as refugees and many would be removed relatively swiftly. Neither of these propositions remains true, but the policies remain in place nonetheless.

The short story here is that we currently do everything we can to marginalise and alienate refugees. Then we grant most of them permanent legal status. And the rest we allow to remain but unlawfully. And then some people complain that refugees aren’t integrating properly and can only get jobs as Deliveroo riders.

There are some really easy, cheap and meaningful wins here.

Speed up asylum decisions. The limbo status asylum seekers endure while awaiting a decision is particularly gruesome and punishing. They are isolated from their communities, housed in poor accommodation and given destitution-level support and prevented from working or studying. As a bare minimum reform, that limbo period should be made absolutely as short as possible. Genuine refugees can then get on with their lives and removal of failed asylum seekers is (slightly) less painful if they haven’t been resident for a long time.

Allowing asylum seekers to work would ameliorate the effects of these waiting times. Personally I see no particular need to give asylum seekers the right to work if their wait for a decision is a short one. But if it is longer than six months then permission to work and to rent accommodation should be granted. It would reduce asylum support costs for the initial application and appeal stages. It would also help ease asylum seekers into the labour market in a more organic, controlled way than the current approach of giving them seven days to find a job or be homeless once they are eventually recognised as a refugee.

There’s no need to force refugees to wait five years for settlement as we do at present. I wouldn't put this as one my highest priorities, given that they almost all achieve settlement in the end anyway, but it would be better for refugees and their potential employers to know that they have security of status. Employers are reluctant to offer good jobs or training to those with what looks like temporary status because it has a expiry date. I know that almost all refugees will get to stay permanently. But that isn’t how it looks to ordinary people looking at proof of immigration status that expires on a set date.

Granting immediate settlement would be far more pragmatic, realistic and useful. After all, zero refugees have ever been removed because their country has later been declared safe since that policy was introduced in 2005. Before that, refugees were granted settlement at the same time as refugee status. If a refugee commits a criminal offence, they would still be subject to deportation as at present, if their home country had become safe in the meantime.

And it would reduce Home Office workload by removing the need to make a second, later decision in each case.

In short, stop designing the system to prevent refugees integrating. But there are other things that could also be changed at no or relatively low cost.

The transition from asylum seeker to refugee status could be considerably improved. Allowing asylum seekers to work would already be a big step in the right direction for some but more could be done for others. The move-on period from asylum seeker to refugee status could be extended a little, as the Red Cross has advocated.

Refugee family reunion could be streamlined and improved. It’s a mess at the moment and beset with delays. Relatively small amounts of funding could really help some very vulnerable people and help refugees get on with their lives with their family around them, rather than worrying about them and having to work for months or years to achieve reunion.

English language lessons would be useful and that doesn’t involve big money either. Asylum support and accommodation should be improved. Housing refugees in barracks and barges should be stopped.

I’m sure there are other things campaigners can think of on this front. I’m writing this in a hurry and these are just some ideas that have been swirling around in my head!

If these ideas are implemented, we would have a functioning asylum system which helped refugees get on their feet. We would also have a sense of control of the border.

In some ways that’s not very radical at all.

But if you compare it to the cruelty of the Rwanda scheme and the chaos of the perma-backlog the Illegal Migration Act will inevitably create then it looks pretty radical.

Apologies if there are more typos than normal here. I’ve ended up adapting and re-writing this from a draft I was working on because of today’s news. And I’ve got Covid, which hasn’t helped!